June 20: Ode to the Spittlebug

Some of my earliest childhood memories are of specific things in nature that I was fascinated with. The marvelous seed dispersal technique of Jewelweed, where just brushing up against a seedpod would create a delightful explosion of seeds. The unique housing of the Caddisfly larvae, an aquatic insect that builds a protective case from slivers of sticks or tiny pebbles. The disgustingly interesting home of the Spittlebug nymph, which was found in abundance in the overgrown fields near the old farmhouse I grew up in.

Some of my earliest childhood memories are of specific things in nature that I was fascinated with. The marvelous seed dispersal technique of Jewelweed, where just brushing up against a seedpod would create a delightful explosion of seeds. The unique housing of the Caddisfly larvae, an aquatic insect that builds a protective case from slivers of sticks or tiny pebbles. The disgustingly interesting home of the Spittlebug nymph, which was found in abundance in the overgrown fields near the old farmhouse I grew up in.

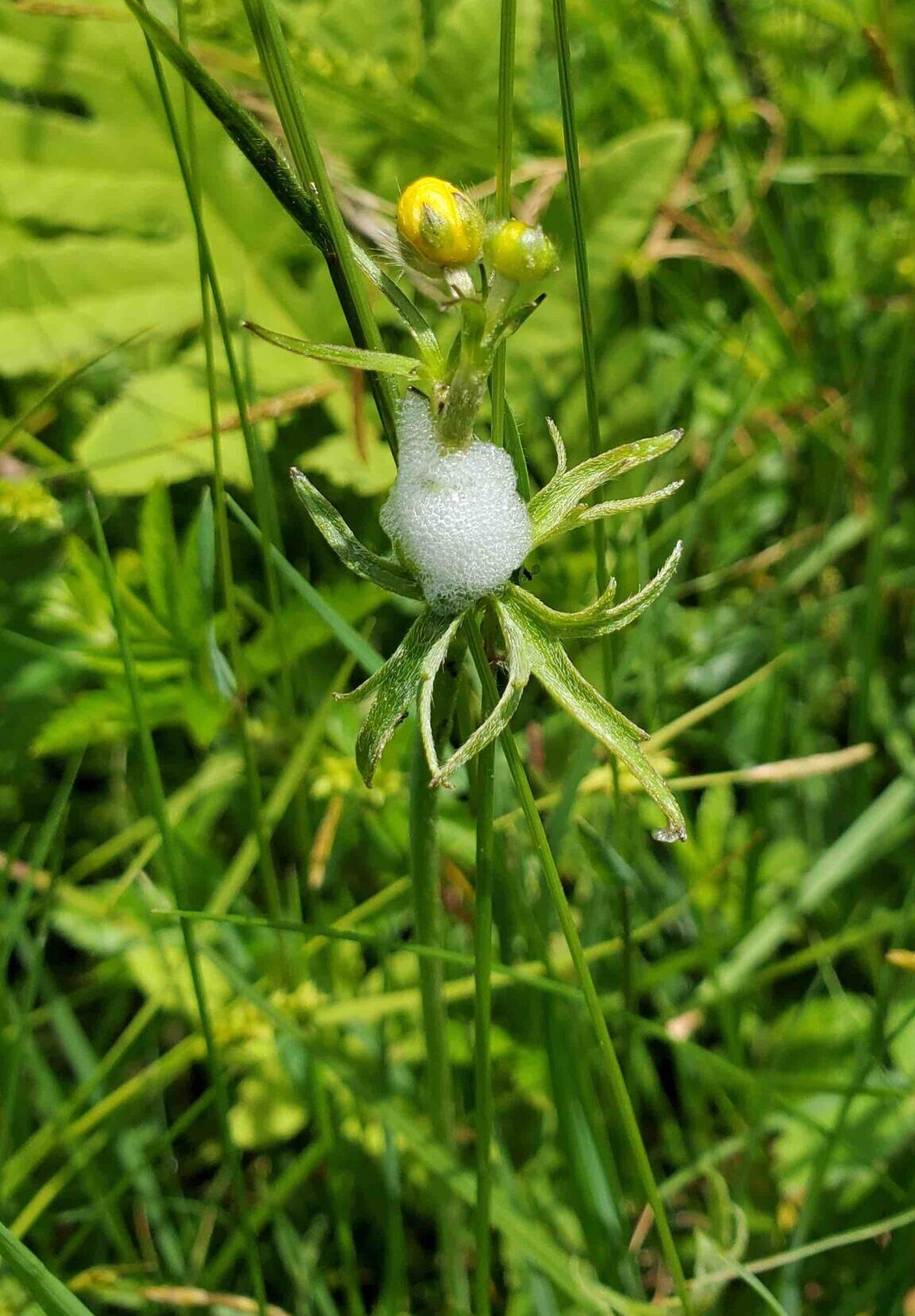

While walking through the old pastures at Oak Point Farm a few days ago I was taken back to this childhood fascination, as seemingly overnight, many of the emerging goldenrods, buttercups, hawkweed, and other plants appeared to be coated in gobs of “spittle”. Sometime in May, unbeknownst to me and others walking by, the eggs laid last summer by a spittlebug mother hatched from the leaf litter. That tiny spittlebug nymph started feeding at the base of plants and kept moving up, eventually settling near some tender leaves or flowers and creating its telltale home.

Spittlebugs are not picky eaters. They feed on plant sap from a variety of flowers and grasses. Spittlebug nymphs suck fluid from the xylem, which is the main water-carrying structure of the plant. The foam they create isn’t actually spittle from their mouths, but rather large amounts of watery urine combined with some sticky fluid. They create the blob of bubbles by pushing air from their rear end, mixing it with the liquid, and then piling the results up on their backs.

There are a number of advantages for surrounding oneself in bubbles. Most obvious is that the birds and other predators that would like to eat bugs will be turned off by the “spittle”. Other advantages include temperature regulation and protection from drying out. Eventually the spittlebugs retreat into one large bubble and undergo a transformation to emerge as their other common name, “froghoppers”. During this transformation, the foam dries and becomes less of a barrier. By the time the froghopper is ready to leap away, the spittle is powdery, and those of us walking by are unlikely to notice them.

As adults they move to nearby grassy areas, where they use their enlarged hind legs to jump many times their height and length, helpful when evading predators. We have several species of spittlebugs in Maine, with the Meadow Spittlebug being common. They’re about ¼ inch long but are not usually seen. They are similar to leafhoppers but appear fatter. In September and October, the females with return to the leaf litter to lay more clusters of eggs. There is only one generation per year, but their stretch as spittlebugs lasts up to eight weeks, so be sure to keep an eye out for them the next time you visit a BRLT preserve or even in your own backyard.