Burning bush is known for the corky structures or ‘wings’ on the side of the stems.

Over the past few weeks, I have become accustomed to quizzical looks from visitors at Ovens Mouth Preserve. Standing many feet off the trail observing plants, making notes on a clipboard, and typing information into my phone, I must have appeared odd and perhaps a bit startling to the unsuspecting hiker who happened upon me. In fact, I have been hard at work mapping invasive plants on the preserve as part of Boothbay Region Land Trust’s management effort. The hope is to better understand the scope of invasive plants at Ovens Mouth in order to inform the land trust’s management plan and to mitigate their future spread.

Invasive plants can do untold damage to the biodiversity of Maine woodlands as their excessive growth takes away water, space, and sunlight from diverse native populations. BRLT selected Ovens Mouth East for invasive mapping work due to a particularly intense stand of burning bush (Euonymus alatus) in the middle of the preserve. If you have recently been on the center trail at the preserve, you may have noticed this tall shrub growing thickly along the sides of the trail. The area of burning bush was a shock the first time I saw it. As a botany student I am familiar with burning bush, having seen it under control in gardens or as a few isolated plants in the woods of Connecticut. I did not understand how intensely the plant could take over until I saw its growth at Ovens Mouth. I also noticed bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) and non-native shrub honeysuckle populations widespread in the preserve. With a clear sense that Ovens Mouth was a prime preserve to target invasive growth, the next steps involved much closer investigation.

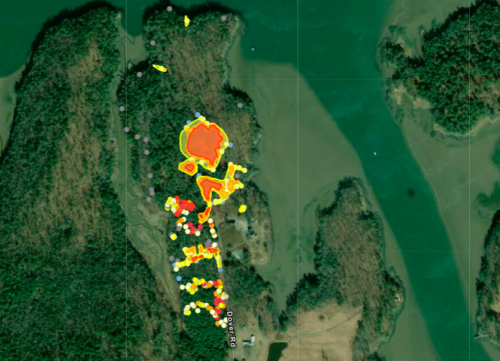

My course studies at Connecticut College included both invasive plants and digital mapping, so this project presented a great opportunity to apply my skills. The mapping process required first walking the perimeter of the infested areas at Ovens Mouth, and then recording the approximate invasive plant population density along with GPS coordinates. Next, I loaded the data onto the computer and used mapping software to place points on a digital map. Finally, I had to ‘connect the dots,’ creating concentric shapes on the map to represent the severity of invasive growth in a given area. This map will be an important first step in controlling invasive growth at the preserve.

Bittersweet (vine in front) climbing a non-native honeysuckle (plant with red berries). Both plants are invasive.

Populations of certain invasive plants can explode rapidly due to favorable conditions and a lack of natural predators. Even a single fallen tree that exposes the understory to more light can cause an extreme population increase. This opportunistic ability gives many invasive plants an advantage, but can do damage to native ecosystems. Some invasive plants can actively harm other plants, such as the vine bittersweet. Bittersweet is known to climb trees and often kills its host by wrapping too tightly, blocking the host tree’s leaves from obtaining sunlight, or breaking branches with its weight. Invasive plants also indirectly cause harm to ecosystems by blocking the growth of native plants that are vital to wildlife as food sources and shelter.

As the invasive plants in the preserve are located and removed, the hope is that the area can become available to many more species of native plants, which will better support native ecosystems. Invasive plants are difficult to remove entirely because many plants have the ability to regrow from cut roots left in the ground. The best non-herbicide treatment is to continually cut back new growth until the roots run out of stored energy. Since Ovens Mouth is not an isolated system the invasive plants can always return from neighboring areas, but with careful annual monitoring and removal the population can be kept under control. This is a process that can take several years to see change, but overtime will become increasingly manageable. So, the next time you are walking at Ovens Mouth Preserve, keep an eye out for invasive plants and do not be afraid to say hi if you see me busy with my clipboard and phone off the trail.

Claire Pellegrini is Boothbay Region Land Trust’s 2020 Conservation Intern and a rising senior at Connecticut College.